| Complications |

The effects of bronchodilators, including the side effects, occur as a result of the aerosolized medications being absorbed into the circulation. The most common complications experienced in relation using adrenergic bronchodilators include:

|

Side Effect |

Cause |

|

Increased heart rate |

beta1 stimulation |

|

Arrhythmias, palpitation |

beta1 stimulation |

|

Skeletal muscle tremor |

beta2 stimulation |

|

Anxiety, nervousness, insomnia, nausea |

beta2 stimulation |

|

Decreased PaO2 (occasional) producing |

beta2 vasodilation altered V/Q |

While all patients using adrenergic bronchodilators will experience one or more of these side effects, some will be more sensitive to the adverse effects than others. Careful monitoring is essential when treating respiratory patients with adrenergic bronchodilators, and should include:

· assessment of pulse and respiratory rate before, during and after treatment

· auscultation of lungs before and after treatment

· observation for systemic symptoms of side effects such as tremor, sweating, or fatigue

Treatments should be suspended or terminated should serious side effects occur.

In this section of this continuing education course, we will look at some of the more common drugs used for treating respiratory diseases and present you with some articles (or excerpts from articles) that have been published regarding these drugs. The list is by no means comprehensive, but is intended to give you some information to review regarding these drugs, what has been written about them, and how they are used in respiratory care. Drugs are listed alphabetically by generic name. Trade names appear in parentheses after the generic names.

· Albuterol (Proventil)

· beclomethasone dipropionate (Vanceril)

· budesonide (Rhinocort, Pulmicort)

· cromolyn sodium (Intal)

· Dnase (Pulmozyme)

· Flunisolide (AeroBid)

· fluticasone propionate (Flonase)

· montelukast (Singulair)

· pranlukast (Ultair)

· salmeterol (Serevent)

· terbutaline (Brethaire, Brethine, Bricanyl)

· theophylline

· triamcinolone acetonide (Azmacort)

· Viozan

· Zafirlukast (Accolate)

(No. 237; pp. 12-15) of Medical Sciences Bulletin

|

Drugs Used for Asthma |

|

|

|

Generic Name |

Trade Name(s) |

|

|

Bronchodilators: Beta2-Agonists |

||

|

albuterol |

Proventil, Ventolin |

|

|

Bronchodilators: Other |

||

|

theophylline |

Various |

|

|

Mast Cell Inhibitors |

||

|

cromolyn sodium |

Intal |

|

|

Corticosteroids: Metered-Dose Inhaler |

||

|

flunisolide |

AeroBid |

|

|

Corticosteroids: Oral |

||

|

methylprednisolone |

Various |

|

|

Leukotriene Inhibitors or Antagonists |

||

|

zafirlukast |

Accolate |

|

|

Anticholinergics |

||

|

ipratropium bromide |

Atrovent |

|

The introduction three decades ago of bronchodilating beta2-agonists — adrenergic agonists selective for the beta2 receptor — revolutionized the treatment of asthma. These agents proved to be more potent and longer acting (4-6 hours) than the nonselective adrenergic receptor agonists such as isoproterenol, which stimulate both alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors. Beta2-agonists give rapid symptomatic relief and also protect against acute bronchoconstriction caused by stimuli such as exercise or the inhalation of frigid air. Frequency of use can also serve as an indicator of asthma control. Recently, an extra long- acting beta2-agonist-salmeterol (duration up to 12 hours)-was introduced in the United States. Salmeterol is so potent that it may mask inflammatory signs; therefore, it should be used with an anti-inflammatory.

Theophylline is a relatively weak bronchodilator with a narrow therapeutic margin (blood level monitoring is recommended to avoid toxicity) and a propensity for drug interactions (competition for hepatic cytochrome P450 drug-metabolizing enzymes alters plasma levels of several important drugs metabolized by that same system). On the plus side, theophylline has some anti-inflammatory activity, can be taken orally, and is available in long-acting formulations; patient compliance is good with once- or twice-daily oral formulations.

About 60% to 70% of asthmatics have mild disease that can be managed with inhaled beta2-agonists alone, when pretreatment is provided before allergen exposure or exercise (cromolyn or nedocromil sodium can be substituted). Asthmatics with more severe disease are generally treated with inhaled beta2-agonists as needed, along with other antiasthma medications, in particular, inhaled corticosteroids (regular use of inhaled corticosteroids, but not beta-agonists, has been shown to reduce the number of exacerbations of asthma, even in patients with mild disease). Theophylline is generally reserved for use in conjunction with other antiasthma agents for patients with moderate to severe disease.

Before 1990, beta2-agonists were often administered on a regular schedule, which was thought to provide better asthma control. However, recent studies have shown that scheduled use is associated with poorer control and possibly with increasing asthma mortality worldwide. This association was first noted in the late 1960s with the use of a potent formulation of the nonselective isoproterenol. A second dramatic increase in asthma mortality was associated with the introduction in the late 1970s of a high-dose formulation of fenoterol. Later, frequent use of fenoterol or albuterol (primarily via nebulizer, and not metered-dose inhaler) was found to increase the risk of death in patients with severe asthma.

It is possible that the overuse of inhaled beta2-agonists is simply a marker for severe uncontrolled asthma, and may not be the cause of death. However, it is also possible that the transient deterioration of airway responsiveness observed when the medication is stopped contributes to the risk. Also, beta-agonists have been associated with a rebound increase in bronchoconstrictor response to allergens, and with a partial loss of protection against exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

Several studies have shown that as-needed administration is at least as effective as regularly scheduled administration; therefore, using beta2-agonists on demand is preferred. One recent trial involved 255 patients with mild asthma who received albuterol inhalation therapy either on a regular schedule (126 patients) or as needed (129 patients). The follow-up period lasted 18 weeks, and outcomes measured included peak expiratory flow, forced expiratory volume in one second, asthma symptoms, asthma exacerbations, quality of life, need for additional albuterol, and airway responsiveness to methacholine.

The average total use of albuterol in the scheduled group was 9.3 puffs per day, and in the as-needed group, 1.6 puffs per day. Basically, there were no clinically important differences between the two groups, although bronchodilator response to albuterol was increased in the scheduled-treatment group at the end of the trial. The investigators concluded, “In patients with mild asthma, neither deleterious nor beneficial effects derived from the regular use of inhaled albuterol beyond those derived from use of the drug as needed. Inhaled albuterol should be prescribed for patients with mild asthma on an as- needed basis.”

From issue No. 251 of Medical Sciences Bulletin

Asthma affects 14 to 15 million adults and children in the United States. It is a chronic disease that requires daily supervision by the sufferer. Although it is presently incurable, it is manageable, and a central focus in asthma therapy has been to provide treatment options that provide a better quality of life for patients.

A published clinical trial focused on the safety and efficacy of salmeterol as compared with albuterol; it also assessed the impact each therapy had on the patient’s quality of life.

Salmeterol and albuterol are analogs. Salmeterol is a long-acting, highly selective, beta2-adrenergic agonist that provides up to 12 hours of bronchodilation, which is approximately two to three times that of albuterol. Previous clinical trials have demonstrated salmeterol’s superiority to albuterol in improving pulmonary function and reducing symptoms of asthma. The safety profiles of both drugs are generally similar with both being well tolerated when used as directed.

This randomized, parallel group, multicenter study consisted of 539 nonsmoking subjects, 12 years of age or older, who were diagnosed with asthma. As a requirement, all had been receiving daily bronchodilator treatment for 6 weeks or longer. Eligible subjects had a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) measurement of 40% to 80% of predicted values, which increased by greater than 15% within 30 minutes of inhalation of 180 mcg albuterol, after bronchodilator therapy had been withheld. Subjects were excluded for several reasons, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, current pulmonary infection, hospitalization for asthma within the previous 3 months, and the use of more than two albuterol inhalers per month during one of the previous 3 months.

The study involved 40 clinical sites. A two-week assessment period was followed by a 12-week treatment period. During the first period, baseline assessments were obtained for peak expiratory flow (PEF) rate, asthma-related symptoms, nocturnal awakenings, and use of albuterol aerosol. On the first treatment day, patients were assigned randomly either salmeterol 42 mcg twice daily or albuterol 180 mcg four times daily. Patients were given two metered-dose inhalers that had either active drug or placebo. They were told to take two puffs from inhaler “A” in the morning and at bedtime and two puffs from inhaler “B” in the late morning (11AM and 1PM) and in the early evening (5 and 8 PM). Salmeterol was administered as the first and last dose. All patients used albuterol aerosol when needed to relieve breakthrough symptoms.

Subjects kept rating cards of daytime symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest tightness and wheezing, and nighttime symptoms, including nocturnal awakenings due to asthma. Use of albuterol was also recorded, as were patient-obtained PEF measurements. These were assessed in the morning before the first does of the study drug and in the evening before the last dose of the study drug.

This study showed the enhanced effectiveness of salmeterol over albuterol with regards to quality of life. At the end of the first 4 weeks, a significant improvement in the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire ratings was demonstrated among subjects using salmeterol when compared to albuterol. This trend continued throughout the subsequent weeks of the trial. Albuterol did not meet the criteria for a small change from baseline until week 12, and this occurred in the asthma symptom domain only. However, improvements from baseline were noted in both daytime and nighttime symptom ratings for the salmeterol group. Also, this group experienced a greater mean change from baseline in symptom-free days (28.6%) than did the albuterol group (13.4%).

Salmeterol provides the physician with the ability not only to abate asthma symptoms, but also to improve the quality of the lives of patients with asthma.

1. Wenzel SE, Lumry W, Manning M et al. Efficacy, safety, and effects on quality of life of salmeterol versus albuterol in patients with mild to moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998;463-470.

Paper: A Comparison of Low-Dose Inhaled Budesonide plus Theophylline and High-Dose Inhaled Budesonide for Moderate Asthma

Authors: Evans D, Taylor D, Zetterstrom O, Chung K et al

Summary: Inhaled glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment in patients with moderate asthma. The dose used is usually titrated against symptoms. They are a relatively expensive medication particularly valued for their anti-inflammatory effects on the lungs. Theophylline is an oral bronchodilator used in asthma for over 50 years. Its use is decreasing probably due to a perceived lack of anti-inflammatory effect (although new evidence is challenging this assumption) and fears over toxicity associated with high plasma levels. It is, however, extremely cheap. Recent National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines advise the addition of theophylline (or long-acting beta-agonist) to medium dose inhaled glucocorticoids before initiating the long-term use of high-dose inhaled glucocorticoids. This randomized, double-blind controlled trial from Britain and Sweden investigates the effectiveness of such a strategy.

All patients recruited had typical symptoms of asthma and fulfilled the American Thoracic Society criteria for asthma. Despite treatment with inhaled budesonide 800-1000 mcg daily (or other inhaled glucocorticoid at equivalent dose) patients had continuing asthma symptoms. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was greater then 50% predicted and improved by at least 15% following albuterol inhalation. Following a two-week run-in period, patients were randomized to receive theophylline with lower dose inhaled budesonide or high dose budesonide alone. The theophylline group received twice daily oral theophylline 250 mg (or 375 mg if over 80 kg) and 400 mcg inhaled budesonide. The high dose budesonide group received 800 mcg inhaled budesonide twice daily with a placebo tablet matched to the theophylline.

Study treatment was given for three months. Patients were monitored every three weeks and one week after treatment ended. Lung function tests were performed at each visit and theophylline levels measured. After 12 weeks blood cortisol levels were also performed. Diary cards were completed daily. Peak expiratory flow (PEF), symptoms, and use of rescue albuterol medication were recorded.

Sixty-six patients underwent randomization, 31 in each group completed the study. Mean age was 39 years. Compliance with study treatment was high. Both treatments resulted in improvements in lung function that were sustained throughout the trial. In the high dose budesonide group the FEV1 had increased from 2.50 L to 2.62 L by 9 weeks, in the theophylline group the increase was from 2.48 L to 2.76 L; only the latter increase was statistically significant. PEF measurements increased by the end of the trial significantly in both groups: from 411 to 436 L/min in the high dose budesonide group and from 430 to 464 L/min in the theophylline group. Overall changes in PEF were statistically similar in the two groups, the FEV1 improved more in the theophylline group.

There were significant and similar reductions in albuterol use and home recorded variability in peak flow in both groups. There were small and similar reductions in symptom scores in both groups, it is not clear how clinically important these were. Serum cortisol levels fell significantly from 18.4 mcg/dl to 15.9 mcg/dl in the high dose budesonide group but were unchanged in the theophylline group; the clinical significance of this difference is again uncertain. The median serum theophylline concentration in the theophylline group was 8.7 mcg/ml, which is lower than the usual therapeutic range of 10-20 mcg/dl. There were no discontinuations due to treatment side effects.

The clinical benefits to patients achieved with either regime in this study were arguably small. The median daytime daily use of albuterol fell from around two puffs to around one puff in both groups. Perhaps the patients’ asthma was already too well controlled on study entry to require a significant increase in therapy. The main finding is that there were virtually no significant differences between the two treatment regimens in any of the outcome variables measured. Long-term outcomes were not recorded, over time differing anti-inflammatory effects may produce more of a divergence. These results suggest that the addition of low-dose theophylline to inhaled glucocorticoid is at least as good as increasing the dose of inhaled glucocorticoid. It can be done without significant risk of toxicity occurring and is very much cheaper.

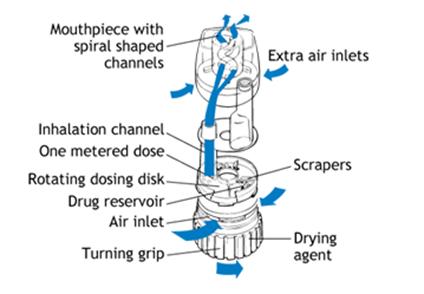

Mar. 31, 1998: A dry-powder inhalation device, the Turbuhaler, performed well in three company-sponsored studies:

.

New Aerosolized Drug Formulations

The past few years have seen the introduction of a variety of new medications focused on preventing or controlling the inflammation associated with asthma. These new medications include the mediator antagonists zafirlukast (Accolate), montelukast (Sigulair) and zileuton (zyflo) are orally administered medications that block the mediator cascade that ultimately results in airway inflammation. Also recently introduced are the aerosolized corticosteroid fluticasone (Flovent) and budesonide (Pulmicort), topically administered glucocorticoids that serve to reduce the inflammatory response.

Additionally, new methods of aerosolized drug administration have been developed in an effort to reduce the liberation of chlorofluorcarbons (CFCs) into the environment by metered dose inhalers (MDI). Currently available in the United States is a non-CFC MDI propellant and various methods for the delivery of dry inhalation powder. The beta agonist albuterol is avail- able as the Proventil HFA MDI and as Ventolin Rotacaps dry inhalation powder. The long-acting beta agonist salmeterol is available as a dry inhalation powder in the Serevent Diskus inhhaler. Fluticasone will soon be available as a dry inhalation powder in the Flovent Diskhaler.

As novel aerosolized medication delivery systems are developed, it is crucial that the respiratory care practitioner understand the correct use of any new device. Significant differences exist in the operation of the various delivery systems. As more devices become available to our patients, the possibility of treatment failures or suboptimal therapeutic response related to improper device use is potentially enhanced. As an example, the use of the relatively new Pulmicort Turbuhaler is significantly different from the similar appearing Ventolin Rotacap inhaler. Without appropriate instruction and follow up from a knowledgeable practitioner, the likelihood that confusion regarding the use of the various new devices will be quite high

Another New Kid on the Block

Pulmicort Turbuhaler (Astra USA. Inc.)

(budesonide

inhalation powder).

Budesonide is anti-inflammatory corticosteroid exhibiting potent glucocorticoid activity and weak mineralocorticoid activity. Inhaled budesonide demonstrates a high topical anti- inflammatory potency. Systemic corticosteroid effects of the inhaled drug are minimized due to extensive first pass hepatic metabolism of any orally absorbed drug, and the low corticosteroid potency of the metabolites.

Inhaled budesonide is indicated in the maintenance therapy of asthma in adult and pediatric patients six years of age or older. Inhaled budesonide is contraindicated in the treatment of acute bronchospasm. The dosage of Pulmicort Turbuhaler is dependent on the patient’s current asthma therapy, and may range from 200 mcg - 800 mcg twice daily.

The Pulmicort Turbuhaler initially contains 200 doses of 200-mcg budesonide per dose. The Turbuhaler device consists of a number of assembled plastic components. The delivery device incorporates a medication storage unit, a dosing mechanism, and a mouthpiece. A brown turning grip, used to release the medication from the storage unit, is positioned at the base of the device, opposite the mouthpiece. A dose indicator window is on the side of the device, just below the mouthpiece. When twenty doses remain, a red mark appears in the top of the window. When the red mark reaches the bottom of the window, the device is empty of medication. A tubular plastic cover screws onto the inhaler to protect the device when not in use.

The basic use of the Pulmicort Tubuhaler is outlined below (note: prior to providing patient instruction, the Practitioner should read the complete prescribing literature provided by the manufacturer):

· Prior to initial use, the device must be primed. The cover is removed, the device is held upright (mouthpiece up, brown turning grip down), and the brown grip is twisted fully to the right and back again to the left. Repeat. The device is ready for initial use. The priming procedure does not need to be repeated.

· To load a dose, the cover is removed and the device is held upright (to properly load the dose, the device must be in the upright position - mouthpiece upright, brown turning grip down). Twist the brown grip fully to the right as far as it will go, then twist it back fully to the left. An audible click will be heard.

· The patient must be carefully instructed not to shake the device once a dose is loaded. In addition, prior to inhaling the dose, the patient should exhale away from the device.

· When inhaling the medication, the Turbuhaler must be in the horizontal position. The mouthpiece should be placed between the lips, with the teeth apart. A seal around the mouth- piece should be formed, and the patient is instructed to inhale deeply and forcefully. A breath hold is not required. Repeat the above sequence for additional doses.

· When dosing is complete, replace and secure the cover on the device. As with any inhaled corticosteroid, the patient must rinse their mouth with water following therapy.

· The Turbuhaler should not be used with a spacer/holding chamber.

According to manufacturer’s instructions:

How to Use a Turbuhaler®

A Turbuhaler® is a dry-powder inhaler available in an easy-to-use format.

Some Turbuhalers® feature a dose counter that shows the exact amount of medication left. If the Turbuhaler® doesn’t have a dose counter, then check for a red indicator in the windows on the side of the device. When red can be seen in the window, there are approximately 20 doses left and it’s time to order a refill.

How to use a Turbuhaler®:

If one drops the Turbuhaler® or breathe into it after its dose has been loaded, it may cause the dose to be lost. If either of these things happens, reload the device before using it.

Clean the Turbuhaler® as needed. To do this, first wipe the mouthpiece with a dry tissue or cloth. Never wash the mouthpiece or any other part of the Turbuhaler® - if it gets wet, it won’t work properly.

National trends in asthma visits and asthma pharmacotherapy, 1978-2002 Pediatrics, August, 2004 by Jenny Campbell, Stacie M. Jones

Purpose of the Study. To analyze asthma clinic visits and changes in asthma pharmacotherapy during a 25-year period.

Study Population. Subject data from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index, from 1978 to 2002, were used to evaluate asthmatics examined by office-based physicians.

Methods. The National Disease and Therapeutic Index provides data on diagnostic and prescribing information from physicians across the United States. Approximately 3500 physicians participate each 3-month period and provide information on patients they examine in 2 consecutive workdays. Information focuses on specific diagnoses and medications, not on patient adherence. This study analyzed the number of asthma visits (based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, codes) and medications used to treat asthma each year from 1978 to 2002, primarily in an outpatient setting. Medications were classified as controllers (eg, inhaled corticosteroids) or relievers (eg, short-acting,[[beta].sub.2]-receptor agonists).

Results. The annual number of patient visits for treatment of asthma doubled from 1978 (8.5 million) to 1990 (17.7 million) and then demonstrated a plateau, with a mean of 16 million cases per year, from 1991 to 2002. The treatment of asthma changed tremendously during the 25-year study period. Prescription rates for controllers increased; in 2001, controllers were prescribed more than relievers (83% vs 80%) for the first time. Prescriptions for relievers increased from 1978 to 1993 but decreased thereafter. From 1978 to 1988, prescriptions for inhaled corticosteroids remained at 8% with respect to the annual total of asthma visits. This number increased to 48% in 2002. The use of long-acting, [[beta].sub.2]-receptor agonists alone peaked in 2000 and declined to 9% in 2002, most likely because of increased use in combination with inhaled corticosteroids (20% of visits). The use of leukotriene modifiers steadily increased after their release in 1997, to 24% in 2002, whereas xanthine use decreased to 2% and cromone use decreased to <1%. Oral corticosteroid use was constant at 20%. The number of medications was stable, at a mean of 2 per patient, during the past decade.

Conclusions. The study concluded that, although the number of asthma visits increased during the study period, the number of return visits for treatment of asthma decreased. Prescriptions for controller medications increased, whereas prescriptions for relievers decreased. This pattern suggests that asthma treatment is changing to be more consistent with current guidelines.

Reviewers’ Comments. Consensus guidelines for asthma are helpful for adequate diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Trends in asthma pharmacotherapy are changing, so that controller medications are prescribed more often, leading to decreased need for relievers and better control of asthma. This study did not include asthma-related visits to emergency departments or hospital-based clinics; therefore, more severe cases of asthma might not have been adequately analyzed.

Apr. 27, 1998: Asthma and side effects of inhaled corticosteroids are covered in these recent articles:

Reprints not available.

Reprints: K. S. L. Lam, U. Dept. of Med., U. Hong Kong, Queen Mary Hosp.,

Pokfulam, Hong Kong.

Reprints: W. Busse, U. Wisconsin-Madison Med. Sch., Madison, WI 53792.

Reprints: L-P Boulet, Hopital Laval 2725, Chemin Sainte-Foy, Quebec G1V 4G5, Canada.

According to the National Jewish Asthma Information Web site in 2005:

Corticosteroids (steroids) are medicines that are used to treat many chronic diseases. Corticosteroids are very good at reducing inflammation (swelling) and mucus production in the airways of the lungs. They also help other quick-relief medicines work better.

The steroids (corticosteroids) used to treat asthma and other chronic lung diseases are not the same as anabolic steroids, used illegally by some athletes for bodybuilding. Corticosteroids do not affect the liver or cause sterility.

Corticosteroids are similar to cortisol, a hormone produced by the adrenal glands in the body. Cortisol is one of the body’s own natural steroids. Cortisol is essential for life and well being. During stress, our bodies produce extra cortisol to keep us from becoming very sick.

Normally the adrenal glands release cortisol into the blood stream every morning. The brain monitors this amount and regulates the adrenal function. It cannot tell the difference between its own natural cortisone and that of steroid medicines. Therefore, when a person takes high doses of steroids over a long time, the brain may decrease or stop cortisol production. This is called adrenal supression. Healthcare providers generally decrease a steroid dosage slowly to allow the adrenal gland to recover and produce cortisol at a normal level again. If you have been on steroids long-term do not stop taking them suddenly. Follow your doctor’s prescription.

Steroid medicines are available as nasal sprays, metered-dose-inhalers (inhaled steroids), oral forms (pills or syrups), injections into the muscle (shots) and intravenous (IV) solutions. Healthcare providers at National Jewish rarely use steroid shots for the treatment of chronic lung disorders. With severe episodes or emergencies, high-dose steroids are often given in an IV. As the symptoms improve, the medicine is changed from IV to oral forms and then slowly decreased.

Inhaled steroids and steroid pills and syrups are often prescribed for people with a chronic lung disease.

Common inhaled steroids include:

An inhaled steroid is typically prescribed as a long-term control medicine. This means that it is used every day to maintain control of your lung disease and prevent symptoms. An inhaled steroid prevents and reduces swelling inside the airways, making them less sensitive. It may also decrease mucus production. An inhaled steroid will not provide quick relief for asthma symptoms. In addition, inhaled steroids may help reduce symptoms associated with other chronic lung conditions.

Healthcare providers may adjust the dosage of inhaled steroid based on a patient’s symptoms, how often they use quick relief medicine to control symptoms and their peak flow results. The patient still may need a short burst of oral steroids when they have more severe symptoms.

The most common side effects with inhaled steroids are thrush (a yeast infection of the mouth or throat that causes a white discoloration of the tongue), cough or hoarseness. Rinsing the mouth (and spitting out the water) after inhaling the medicine and using a spacer with an inhaled metered-dose-inhaler reduces the risk of thrush. When a dose is prescribed that is normal or higher than the normal dose in the package insert, some systemic side effects may occur. Keep in mind, however, that an inhaled steroid has much less potential for side effects than steroid pills or syrups.

Common steroid pills and syrups include:

Steroid pills and syrups are very good at reducing swelling and mucus production in the airways. They also help other quick-relief medication work better. They are often necessary for treating more severe respiratory symptoms.

Steroid pills and syrups can be used as a short-term burst to treat severe respiratory symptoms. They may also be used as part of the routine treatment for chronic lung disease.

Many people with chronic lung disease need a short burst of steroid pills to decrease the severity of symptoms and prevent an emergency room visit or hospital stay. A burst may last two to seven days and not require a decreasing dose. For others, a burst may need to continue for several weeks with a decreasing dose. This is called a steroid taper. Common side effects include increased appetite, fluid retention, moodiness and stomach upset. These side effects are short-term and often disappear after the medicine is stopped.

Some people with a chronic lung disease require the use of steroid pills or syrups as part of their routine treatment for weeks, months or longer. In several lung diseases, the main treatment is high-dose steroid pills for several months or longer. If the patient has asthma, it is important that treatment include an adequate dosage of an inhaled steroid before beginning routine steroid pills. We recommend that anyone requiring routine steroid pills be under the care of a specialist (pulmonologist or allergist).

The use of routine steroid pills or frequent steroid bursts can cause a number of side effects. Steroid side effects usually occur after long-term use with high doses of steroid pills. Side effects, which may occur in some people taking high-dose steroid pills, include:

|

Side Effects |

Prevention of Side Effects |

|

Endocrine (hormones): · Suppression of the adrenal glands · Delayed sexual development · Changes in menstrual cycle · Increase and change in fat placement causing fullness in the face and weight gain · Increased blood sugar (diabetes) · Emotional changes such as moodiness, depression, euphoria or hallucinations |

Endocrine (hormones): · Your healthcare provider may prescribe your steroid pills at specific times. Make sure you take your steroid pills as prescribed and do not stop them suddenly. · If you have taken oral steroids, talk with your healthcare provider about obtaining a medical alert bracelet. · Talk with your healthcare provider if you are having moodiness or depression that doesn’t seem to get better. |

|

Fluid and Electrolytes · Salt and water retention · High blood pressure (hypertension) · Loss of potassium |

Fluid and Electrolytes · Limit the amount of salt and foods that are high in sodium to prevent fluid retention and swelling. Condiments and processed foods tend to be high in sodium. · Add foods that are high in potassium to your diet. |

|

Eyes · Increased pressure in the eye (glaucoma) · Clouding of vision in one or both eyes (cataracts) |

Eyes · Visit the eye doctor (Ophthalmologist) at least yearly. Inform him or her that you take steroid pills routinely. |

|

Skin · Increase in body hair and acne · A tendency to bruise easily · Thinning of the skin and poor wound healing |

Skin · Ask your healthcare provider about how acne can be treated. · Keep the skin well moisturized. |

|

Nutrition · Increase in appetite · Irritation of stomach and esophagus with possible ulcer symptoms and, rarely, bleeding |

Nutrition · If you are eating more food, be sure you choose low-fat, low-sugar items to control calories. Ask your healthcare provider or dietitian to help you with a specific diet plan. · Eat a well balanced diet that meets the Food Pyramid Guidelines. · Take your steroid dose with food to decrease stomach irritation. |

|

Muscles · Muscle weakness or cramps |

Muscles · Routine exercise may be recommended to prevent or decrease muscle weakness. |

|

Bones · Joint pain (especially as steroids are decreased) · Thinning of bones (osteoporosis) may lead to fractures or compressions, especially of the backbone and the hip · Loss of blood supply to bones (aseptic necrosis) may cause severe bone pain and may require surgical correction |

Bones · To prevent osteoporosis (loss of calcium in the bones), it is important to eat foods high in calcium, such as dairy products. If you need to control calories, low fat dairy products may be used. · Your healthcare provider or dietician may recommend certain supplements, such as calcium, vitamin D and a multi-vitamin. · Weight bearing exercise may also be recommended by your healthcare provider. · Medication may be prescribed to improve osteoporosis. |

|

Immune System · General suppression of the immune system causes an increased risk to a variety of infections, for example chickenpox |

Immune System · Good handwashing · Avoid exposure to any infectious disease. · If you or your child is exposed to chicken pox or measles while receiving oral steroids or high dose inhaled steroids, notify your healthcare provider immediately to determine if any special treatment is needed. |

· Take your long-term control medicines as prescribed to keep your chronic lung disease under good control. This will help decrease the steroid pills to the lowest possible dose.

· Monitor your lung disease. If you notice your peak flow numbers are decreasing, or you are having increased symptoms, call your healthcare provider. A short burst of steroid pills given early may prevent the need for a longer burst if treated later.

| Complications |